Despite growing up in Mexico City, the fifth-largest city in the world, 18-year-old Naia has found navigating Toronto’s subway system confusing since she arrived two months ago.

“It’s like, go North, go West. What’s that?” She laughs. “Like, how am I supposed to know where’s East?”

Although her home city has its own metro, concerns about how safe it is meant Naia has never used it. Now living by herself for the first time and undergoing a foundation year via Navitas at Toronto Metropolitan University, she is enjoying the freedom and challenges that come with moving to a new country.

While reluctant to speak negatively about her home, Naia, like many young people throughout Mexico, sees education abroad as an opportunity to build a more secure life – somewhere she can use public transport without worrying about her safety.

“At some point, when I get my own house and children, I want them to live in a place in which they can walk down the streets and I know that they’re safe,” she says.

The bleak economic prospects for the non-elite, combined with political tensions and heightened safety concerns, are driving young people out of Mexico.

Although the country boasts the second largest economy in Latin America and the 15th largest in the world, economic growth is slow and inequality is widespread. Among its 127 million strong population, some 43% live in poverty.

In addition, violence and organised crime is pervasive, reaching record highs in recent years, with over 32,000 homicides recorded in 2022.

“If your social status and your economic wealth is good, you are a target”

Through education, young Mexicans hope to secure high-paying jobs and build a better, safer life abroad.

“If your social status and your economic wealth is good, you are a target in Mexico,” says Renan Herrera, executive director at education agency Estudiantes Embajadores.

“We have people coming into our office saying, ‘I need to send my daughter or my son abroad because I got the tip that they are going to kidnap him’.”

At the same time, the growing strength of the peso against the dollar is making it more affordable to study abroad – although most Mexican families remain very cost-conscious.

“Four, five years ago, higher education was a very hard sell,” says Han Steen, owner of education agency Universo Educativo. “It has become a lot easier because of the strong peso.”

Agents are keen to emphasise that studying abroad can be a smart financial decision as tuition fees are expensive at Mexico’s top private universities.

This means selecting institutions in relatively affordable destinations, like Canada and the UK, can be more economical than staying in Mexico, particularly when factoring in part-time job opportunities (which come with a much higher minimum wage than Mexico’s US$11.76 per day) and post-study work routes.

Young Mexicans like Naia are also attracted to other countries by the excitement of living abroad and the opportunities this can bring – pull factors that are fuelled by widespread internet access. Mexico is ranked 10th in the world for the daily time spent using social media, averaging 3 hours 21 minutes per day.

“It’s unbelievable,” says Herrera, explaining that posting aspirational videos of students abroad, such as them skiing, has become central to his agency’s marketing strategy. “We get 200 leads from just one Reel.”

As universities in leading destination countries seek to diversify their international student cohorts, Mexico is one of the places that comes up again and again. It features as a priority country in Canada’s international education strategy and as a secondary focus market in the UK’s.

Given the number of institutions competing to recruit Mexican students, those working in the country advise universities to make sure their programs stand out.

“Mexico is a very price sensitive country but at the end, it’s not only the price,” says Herrera. Institutions without a well-known name should focus on promoting their individual program rankings and their connections with industry, according to agents.

“Face-to-face works much better here in Mexico”

“Face-to-face works much better here in Mexico,” adds Alexis Kinzer, pathways director at education agency Blue Ivy Coaching, explaining that aggregators haven’t taken off as much as they have in other parts of the world.

“Here in Mexico, the families are always like, ‘Oh my God, you can put me in contact with someone, like I can meet someone?’ They really want that exclusive treatment.”

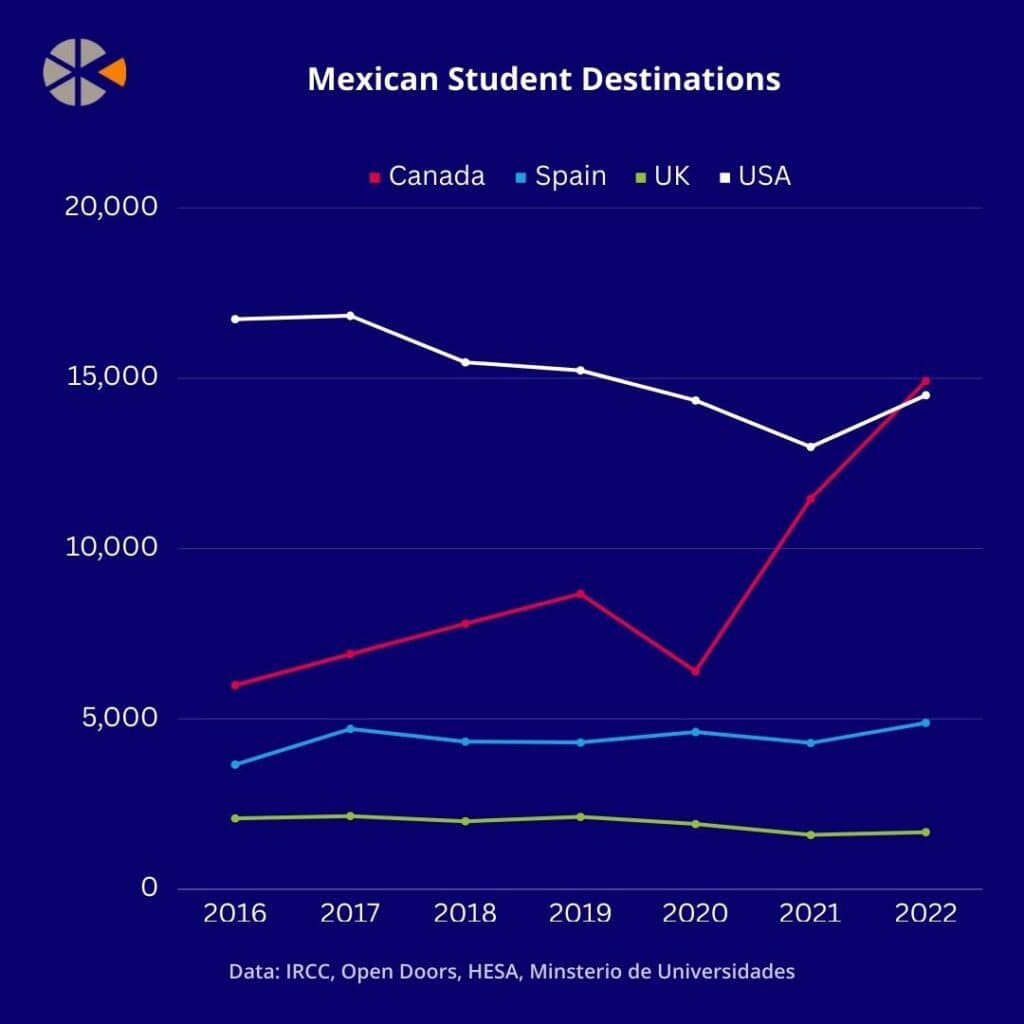

Mexico’s North American neighbours remain popular destinations for students from the country. The number of Mexicans studying in Canada has risen quickly in recent years, reaching an all-time high of 14,920 last year. Students are attracted by the relatively-affordable programs, proximity to home and welcoming reputation.

The opposite is true of the US, which, although still a top receiver of Mexican students, has seen numbers steadily decline from almost 17,000 in 2015/16 to 14,541 in 2022/23. Generally, the US attracts students living in Mexico’s border states, some of whom are eligible for in-state tuition fees.

“All of these states that are near the border of the US typically are students that either have dual citizenship or that their parents work in the US so that they have the funds to go abroad,” says Arturo Segura, regional director for Latin America at Navitas.

But for others, the appeal of the US has declined since the Trump administration and the negative rhetoric towards Mexicans that accompanied his presidency.

“People don’t feel so welcome,” says Steen. “That already starts at the airport and the way they are spoken to and interrogated.”

To really understand the Mexican market, one has to understand the country’s socioeconomic and class divisions, explains Segura.

Prestigious institutions abroad are particularly appealing to Mexico’s upper class, who want the status that comes with attending an Ivy League university or Oxbridge, he says. If they don’t secure a place there, they are more likely to remain in Mexico and enrol at one of the country’s top universities to maintain their inner circle.

“Those students are not looking to migrate,” says Segura. “If you have everything at the tips of your fingers, you don’t want to lose that.”

It is Mexico’s growing middle class who are considering non-elite universities and chances to emigrate permanently. Educating these students about the opportunities abroad is a focus for recruiters working in the country.

“They didn’t really say that studying abroad was an opportunity”

“I’ve studied in Mexico my whole life and I can tell you, at least in my school, they didn’t really say that studying abroad was an opportunity,” says Carla Saviñón, partnerships and events manager at Blue Ivy.

“We start getting ready in 12th grade and that’s when they say, like, ‘Oh, you have to go to college next year’.”

Naia is one of the exceptions to this, having attended a high school which taught the International Baccalaureate, with the goal of applying to foreign institutions. She was partially inspired to study abroad from an early age by her family’s visits to Spain every summer.

“I always had these two worlds,” she said. “I had my Mexican world in which I couldn’t go down the street to buy any candy because, I don’t know, something bad could happen.”

In Spain, she says, she could do whatever she wanted. “Go out to the park or grab my dog and walk him wherever I want. And the safety I could feel there – it’s something that really changed my perspective. Why should I be living in a country in which I cannot do that?”